This week the Rakhine journalist Kyaw San Hlaing – widely seen as an unofficial advocate for the secessionist Arakan Army – claimed that the Rakhine nationalists have gained a notch in their strategic goal of independence from the military-dominated Union of Myanmar, in his op-ed Fighting in Maungdaw: A Strategic Turning Point in Western Myanmar? (The Diplomat, 21 September, 2022). In his words,

“the Myanmar military is currently fighting a multifront war with the rest of the country ‘s resistance forces, creating an opportunity for the Arakan Army to establish its unchallenged control over Maungdaw – and notch a significant milestone on its path toward independence.”

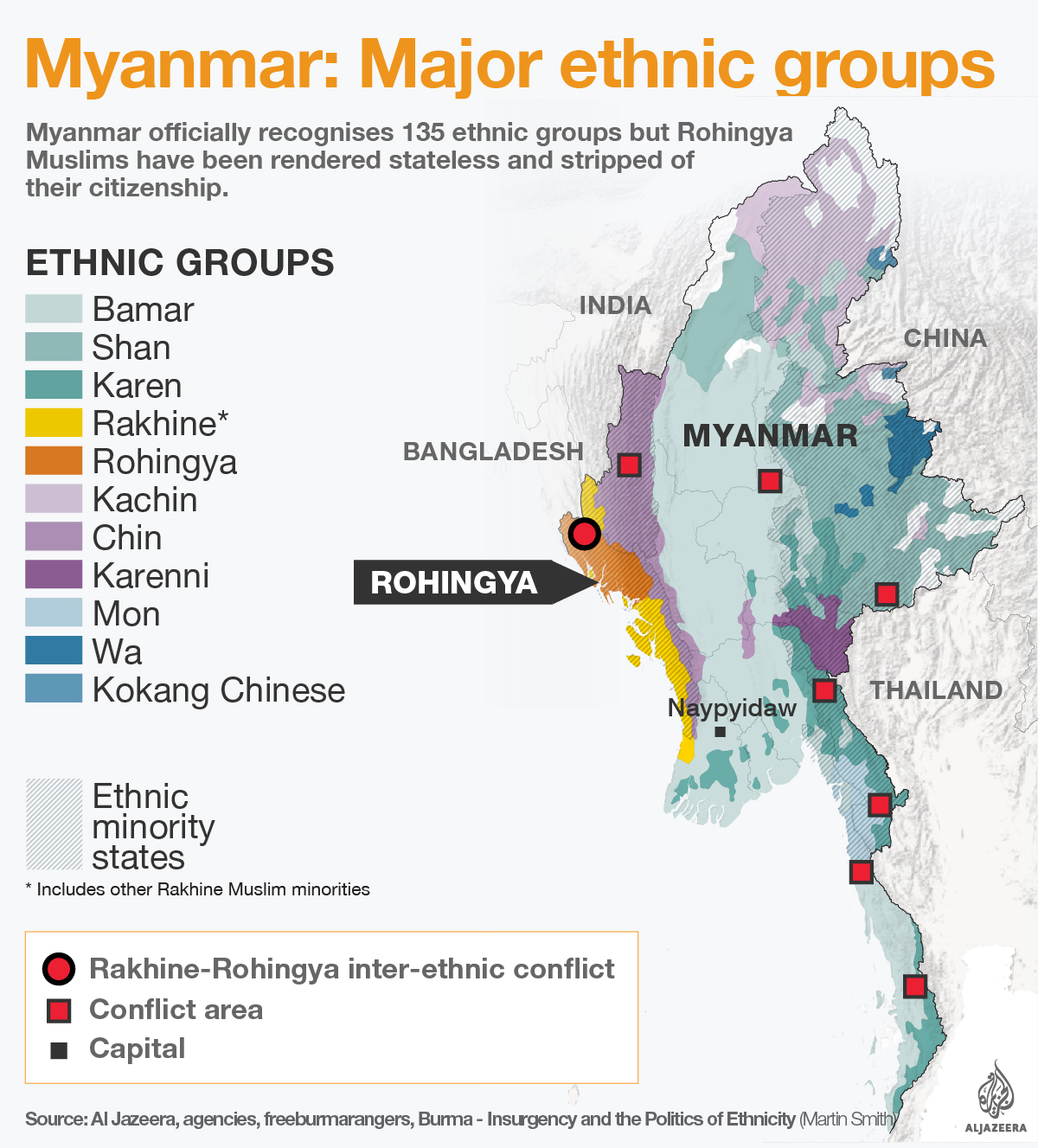

On its part, the Arakan Army leadership, representing, in effect, the interests of the predominantly Buddhist Rakhine population in this Western Myanmar state, adjacent to Bangladesh and across the Bay of Bengal from the eastern shores of India, has openly presented itself to the relevant external actors – such as Bangladesh, India, the UN agencies and so on – as a benevolent alternative to Myanmar military regime, the main architect and perpetrators of the slow-burning genocide of Rohingyas since the late 1970’s.

The Rohingya refugees and campaigners are said to be weary of being used as political pawns by these warring parties – Buddhist Rakhine nationalists in general and Myanmar militarists in power – who only 5-years ago joined forces to wage an atrocious wave of genocidal destruction of Rohingya communities in Western Myanmar. (The Rohingyas are also painfully aware of the fact that Aung San Suu Kyi-led National League for Democracy party was also a genocide collaborator, with Ms Suu Kyi’s infamous defence, not of the genocide victims’ human or citizenship rights, but of their main perpetrators, the Burmese military, at the International Court of Justice in December 2019. The NLD’s post-coup offshoot National Unity Government (in exile) retains ex-genocide deniers in key positions (but this is beyond the purview of this essay).

While the universally opposed military coup of February 2021 has triggered the nation-wide revolt, both peaceful and armed, with virtually segments and ethnic groups across Myanmar Arakan Army (or AA) had effectively assumed strategic neutrality for months. The political and military leaders of the AA had exhorted their Rakhine base to stay focused on their sole mission of regional autonomy, first, and ultimately a complete secession from Myanmar, as an independent sovereign country. Rakhine nationalists rightly see Myanmar as a colonizing central state, which violently ended Rakhine’s kingdom in 1784.

Recent weeks have seen the resurgence of fierce fighting between Myanmar military regime and the Arakan Army in along Bangladesh-Myanmar, which has had spill-over impact in the neighboring Bangladesh. A number of Rohingya refugees on the Bangladeshi soil were killed or injured in the cross-fire between the AA and Myanmar troops. Bangladesh has officially lodged repeated protests against Myanmar’s breach of its land and airspace and the destabilizing developments stemming from the intensifying civil war across the borders in Western Myanmar state of Rakhine. Meanwhile, the Arakan Army and its nemesis Myanmar military are playing the blame games over the border intrusion and the civilian casualties.

In light of the emerging official demand for recognition and acceptance of the Arakan Army (and its political wing United League of Arakan) as the main actor – vis-à-vis Myanmar military – Arakan Army seeks an internationally recognized government.

In the (unlikely) repatriation of 1 million Rohingya genocide survivors who have been languishing in extra-legal and sub-human conditions in refugee camps along the Bangladeshi-Myanmar borders, it is crucial to scrutinize closely the nationalist Rakhines’ public stance on Rohingya, the predominantly Muslim community in Western Myanmar whose ethnic identity and whose right to self-identity Arakan Army refuse to recognize. The Arakan Army’s official statements identify the state’s 2/3 majority Buddhist Rakhines by their chosen ethnic name – as Rakhine – while it continue to call Rohingyas as simply “Muslims”, to the chagrin of Rohingyas worldwide.

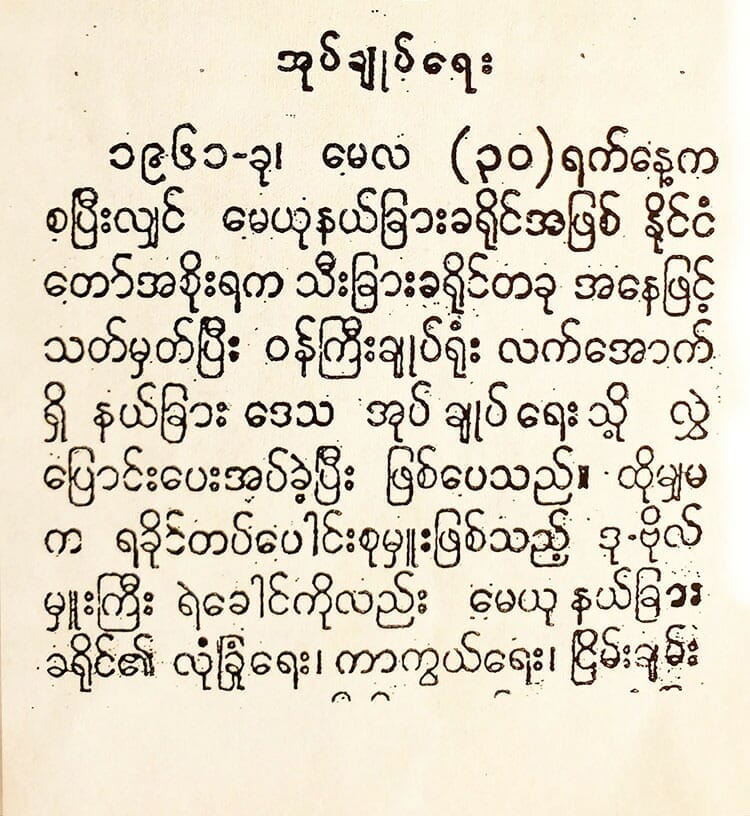

The Bengali print version of the earlier essay by Maung Zarni entitled “Tun Mrat Naing attempts to erase Rohingya identity and history,” Prothom Alo, 9 January 2022.

Continuing Erasure of Rohingya Ethnic Identity

The AA commander and most influential Rakhine leader’s 9 January 2022 interview is a good starting point to assess whether Rakhine leadership respect Rohingya’s right to self-identity and accept the empirical evidence of the group’s historical presence in their shared ancestral birth region.

Rakhine Nationalist Tun Mrat Naing’s carefully worded recognition of Rohingya human and citizenship rights fails to conceal his attempt to erase Rohingya group identity and history, angering the survivors and worrying genocide scholars

Prothom Alo’s interview with Tun Mrat Naing,1 the commander-in-chief of the Arakan Army which spearheads Buddhist Rakhine population’s openly pro-independence movement, comes across as strategically thought-through, determined and sensitive to the discourse of human rights.

But there are some disturbing elements the interview contains which must not go unnoticed. I am writing this paper in the 1st person narrative as my activism and scholarship are deeply intertwined with my own personal and family ties with the military-controlled state in Myanmar.

Therefore, I am writing it not simply as a professional scholar of Burmese politics who has studied the country’s affairs – including inter-ethnic relations and liberation struggles, over the last 30-odd years, but also, importantly, as a Burmese from the dominant ethnic group who unequivocally supports independence aspirations of the internally colonised non-Bama and non-Buddhist ethnic communities, including both Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims. No ethnic community, Rohingyas or Rakhine, should be held in bondage by any other dominant group, against their will.

My Ties with Myanmar Military

In terms of my own personal and family ties with the repressive military regime, the three generations of my own extended military family, both male and female, have, with pride and pratiotism – perhaps misguidedly, in retrospect – served in this national and nationalistic institution since its inception in 1942. One younger brother of my maternal grandfather2 was a close friend and colonial Rangoon University classmate of the founder of the Burmese military and the architect of Burma’s independence, the late Aung San, while the second younger brother3 was the 1st commanding officer of retired dictator Senior General Than Shwe who created the post-General Ne Win quasi-democratic politics that has now run aground. My own mother’s younger brother, Air Force Major Phone Maung, was a VIP pilot who flew General Ne Win’s plane for a quarter of a century since the mid-1970’s until the old dictator was placed under house arrest by Senior General Than Shwe. My late uncle was 15 years senior at the Defence Services Academy to the current Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing.4

The military was originally founded under the patronage of the WWII Japan’s fascist military as a key instrument of liberation struggle against the British colonial rule, which lasted over 120 years. However, the successive post-independence generations of military leaderships5 have succeeded in repurposing the national military and the state as the instruments of control, repression, and exploitation for the exclusive benefit of the military as a ruling class, at great costs to the entire society of multi-ethnic peoples, including the Burmese Buddhist majority.

I will not comment on the Arakan Army chief’s strategic and tactical choices with respect to Rakhine people’s armed struggle to restore the sovereignty lost nearly 250 years ago.

I confine my responses to what I see as factual historical mistakes and omissions, and the unmistakably colonialist orientation – with specific respect to Rohingya people – which I detect in the Rakhine general’s comments.

The Union of Burma and non-Bama Ethnic Revolts against what the Latter Saw as Bama Colonialism and Racism

First, it is factually incorrect to say that previous generations of Rakhine nationalists had only cooperated with the dominant Burmese in the post-colonial Union of Burma, both during the first decade of the parliamentary democracy (January 1948 – March 1962) and the military rule (from 1962 to present, with a short-lived interval of semi-civilian rule of Aung San Suu Kyi).

The sovereignty-conscious Rakhine launched their liberation struggles immediately after the end of the WWII and the military defeat of Japanese Fascist occupational army, which armed and patronised both ethnic Rakhine and Burmese nationalists who signed up to fight against the British, Japan’s target in Burma and India.

In the fall of 1994, I interviewed the late colonel Chit Myint, the acting commander of Burma Rifle Five, who led the military operations against Rakhine’s armed insurrections, one of the two earliest armed revolts, the other of which was the armed rebellion by the Mujahideen, representing the people who have come to identify themselves as Rohingyas in the 1950’s. In the taped interview, he recalled, “My troops were fighting the Rakhine separatists when the whole country was celebrating the transfer of sovereignty from the British Government to the First President of independent Burma in Rangoon on Independence Day (4 January 1948).”6

Major Chit Myaing (far-left front row, in white circle) with a dozen Burmese military including Colonels Maung Maung (red circle) and Aung Shwe (yellow circle), Specialist Weapons School, Warminster, UK, 1947. Maung Maung later became Director of Military Training, responsible for building officers’ training schools and staff colleges in the newly independent Burma.

Additionally, the retired colonel who relocated to Virginia where he lived until his passing several years ago shared his first-hand knowledge of how the senior leadership of the Burmese armed forces planned to militarily pre-empt any armed secessionist movements by any group by building military bases in the country’s non-majority regions such as Shan states in the disguise of military training schools and staff colleges.7

The anti-Shan sentiments – racism, to put it bluntly – in part stemmed from the fact that Shan traditional leaders were known to have openly objected to the post-WWII British leaders such as Labour PM Clement Atlee treating Aung San, the founder of the Burmese military who went to become the most influential nationalist leader, as the representative of the entire Burma made up of different ethnic groups.

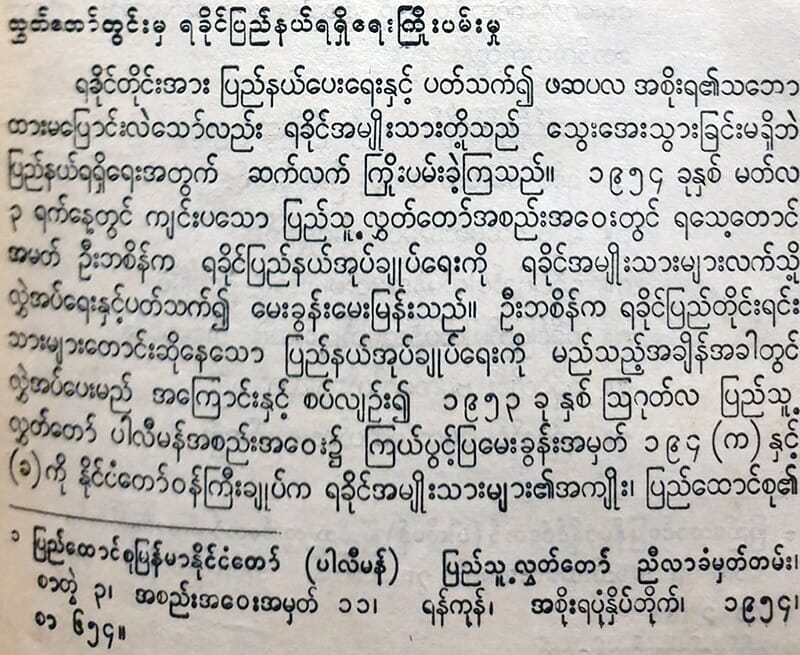

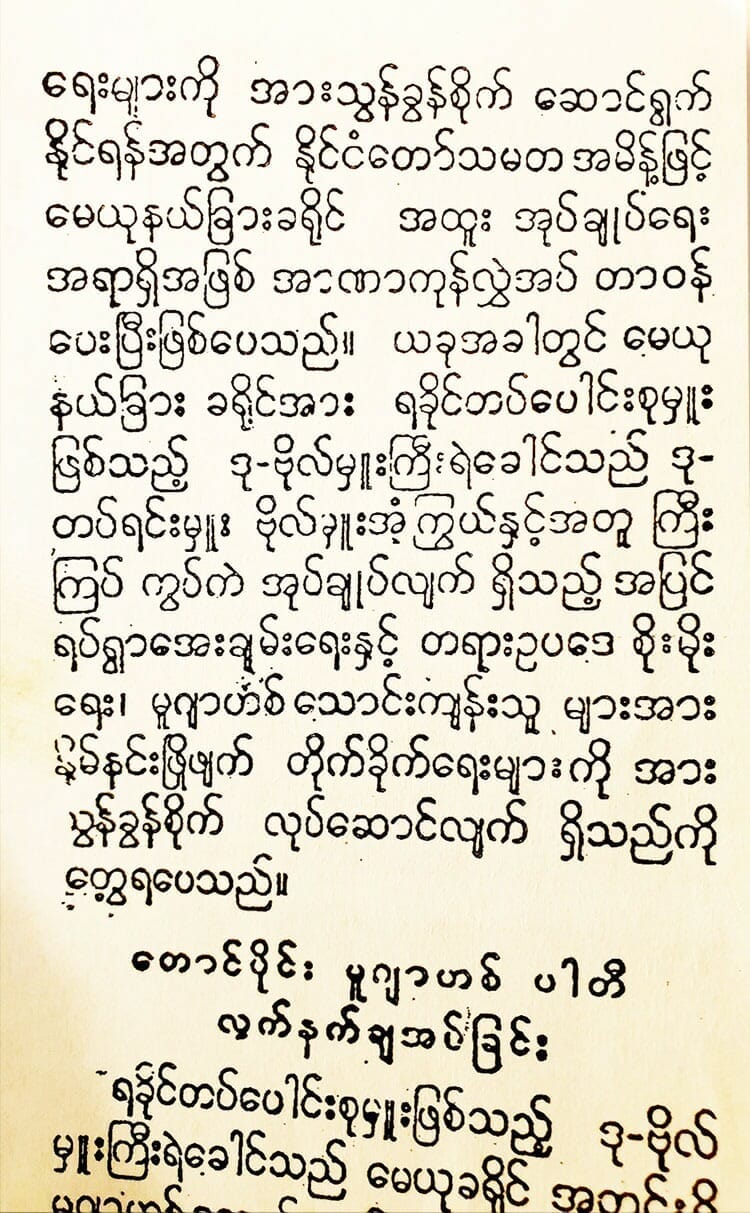

Five days before the pre-dawn military coup on 2 March 1962 launched by General Ne Win, non-Bama ethnic leaders from Shan, Chin, Kayah, Kachin etc. accused the Bama politicians and leaders of being “colonialistic”, displaying ethnic superiority complex known as Maha Bama or the Great Burmese racialism. Source: Man Dai (or Pillar) Newspaper, 25 February 1962.

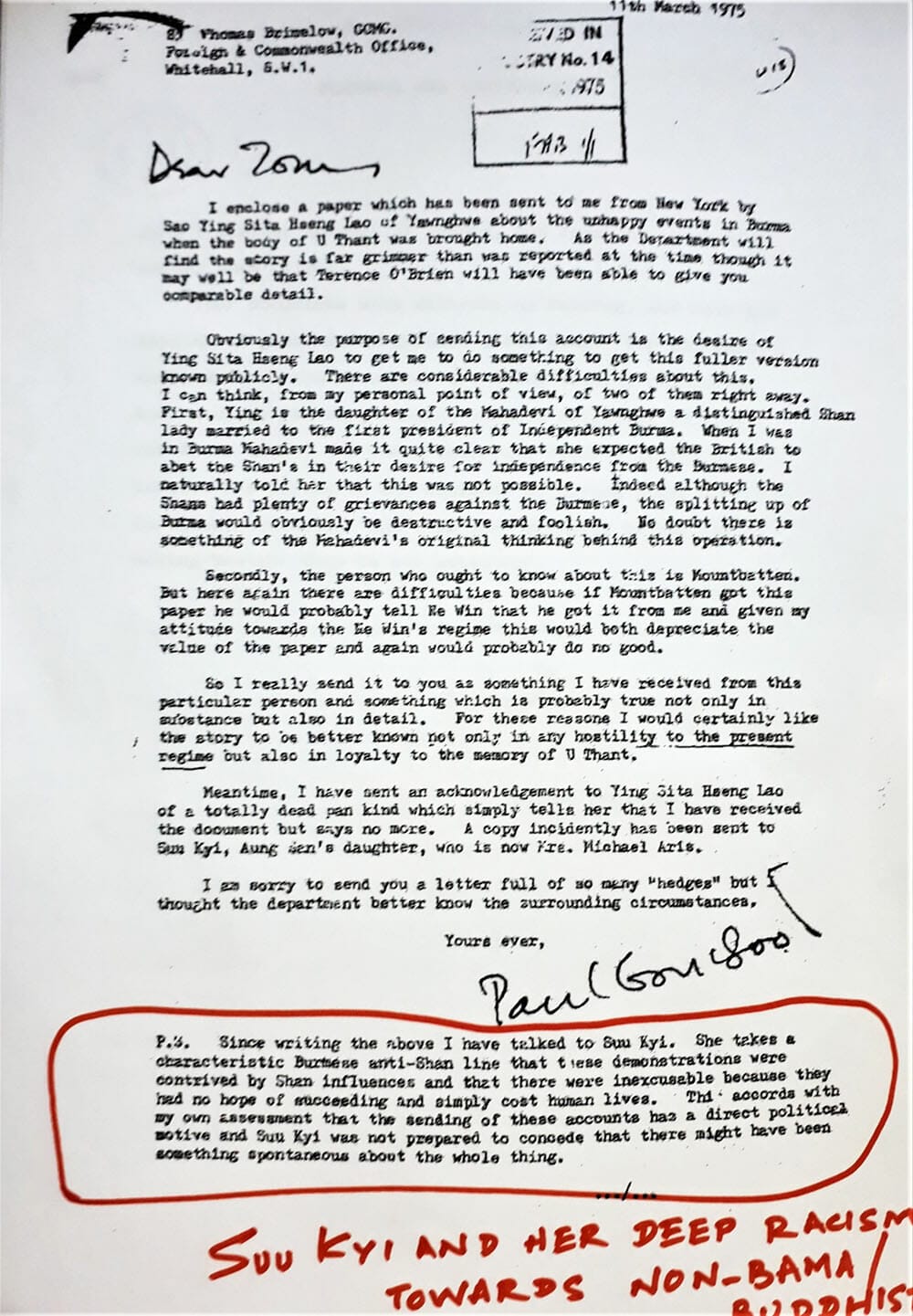

The decades-old accusations of Bama “Big Brother” or Bama Supremacy complex typically made by the national minorities (or ethnic nationalities) are fully justified. Whatever their disagreement, Aung San Suu Kyi and the new generation of generals continue to drink from the same rotten racist-colonial ideological fountains. The following letter (first the relevant excerpt and then the full-text) highlights how pervasive this Bama racism is among even liberally educated elites among the dominant Burmese families.

The 11-March-1975-dated letter was typed-written, signed and sent by Lord Gordon Gore-Booth, a senior British foreign office official and a family friend of Aung San Suu Kyi, to his colleague Thomas Brimelow regarding the anti-dictatorship popular protests in Shan state and Aung San Suu Kyi’s dismissal of them as anything other than events “contrived by Shan influences”

The Emerging Triangular Politics of the So-Called “Center and Periphery”: A New Colonialism

Evidently, outgunned by the central post-independence military led by the likes of Commander Chit Myaing, both early Rakhine liberation movement (and the Rohingya’s attempt to take Northern Rakhine or Arakan state and join the then East Pakistan [since 1971 Bangladesh] in the formative years of Burma as an independent republic) failed categorically.

The parliamentary debates and respective mobilization of group opinions in favour of, and against, seeking autonomous statehood of Rakhine began in the mid-1950’s, with Rakhines pushing for the statehood – within the Union of Burma – and Rohingya, opposing the move and seeking to align their interests with the central ethnically Bama-controlled government in Rangoon.

Source: Kyaw Win, Mya Han and Thein Hlaing (1991) Myanmar Politics (1958-62). Volume 3. pp. 162–255. (Yangon: Central Universities Press). (A compilation and excerpts of official documents and parliamentary records).

Emphatically, because the ancient Arakan and post-independence Rakhine state have always been the shared birthplace and ancestral land between two major ethno-religious communities – namely Rakhine and Rohingya – the understanding of political affairs of Arakan or Rakhine has to be through the prism of this triangular struggle for power over governance of the state – among the colonising Bama (both civilian and military), the locally dominant Rakhine Buddhists and Muslim Rohingyas. Although there are other groups in plains and riverine coastal region of Rakhine such as Chin, Mro, Mranma, Muslim Kaman, etc. they are numerically insignificant to form any power or political bloc in the state’s provincial politics.

Demographically, post-independence Rakhine state ought to be disaggregated and best understood as a cluster of three local political centres, all ethnically defined. These are 1) the northern Rakhine state, historically been the home of the predominantly borderlands people of Rohingyas, with shared linguistic, religious and demographic ties to Bangladesh, a fact which had officially been established and recognized in the Union of Burma government Encyclopaedia (Volume 9, 1964), published two years after the military rule was instituted ; 2) the state’s central sub-region which centres around the two major cities of Mrauk-U, the old seat of Rakhine sovereign kingdom and the main port and administrative city of Sittwe or Akyab is the heartlands of Rakhine people; and 3) the southern part of Rakhine state is home to many of the ethnic Bama internal migrants who have greater ties and loyalty to the central ethnocratic Bama state and government.

There is also the ethnically Chin Paletwa subregion, immediately adjacent to Chin state which borders on India’s north-eastern state of Mizoram.

Throughout the parliamentary democracy period of roughly 14 years – from independence in 1948 to the military coup of 1962, which effectively ended any trappings and space of an electoral democracy, western educated Rakhine politicians in the country’s bicameral parliament in Rangoon campaigned for the autonomous statehood or “internal sovereignty”, to borrow Arakan Army Chief Tun Mrat Naing’s term.8

From the perspective of predominantly Buddhist Rakhine, the Burmese, military and civilian nationalists, are the colonizers, and correctly so. Their prevailing sentiment among the Rakhine, particularly Rakhine elite with a strong nationalist consciousness, is decidedly anti-Bama. The following anecdote may illustrate how strong this nationalist sentiment is.

During my early years as a young student in California in the late 1980’s, I was very close to a US-born Burmese-American atmospheric scientist at my university where he was the only Burmese faculty and I the only Burmese student. His parents were ethnic Rakhine from a very prominent political family who emigrated to USA before the coup of 1962. When I first met his parents visiting him on campus from Hawaii I excitedly asked the father “Uncle, you must speak Burmese”, having triggered a rather irritated response, “No, I don’t speak (your language).” It turned out that this late father of this “uncle” was the late U Kyaw Min9 (the Cambridge-trained member of the Indian Civil Service) who was one of the leaders of Rakhine’s struggle for “internal sovereignty” in the national parliament.

Burmese and Rakhine are linguistic kins with the language overlap of more than 50%. Unlike Mandarin and Cantonese speakers, Burmese and Rakhine peoples can communicate, but in terms of ethnic identity and group consciousness Rakhine do not consider Bama or Burmese their own and vice versa. This is not unlike Chittagongnian Bengali and Myanmar’s Rohingya where in the two groups share a high degree of linguistic commonalities but have two irreducible group identities and consciousnesses.10

After their respective armed rebellions were crushed by the central ethnically Bama-controlled military, both Rakhine and Rohingya politicians used the emerging parliamentary space as the site of their respective struggles for a fair share of power and governance in Rakhine.11

Respectively, “Buddhist” ethno-nationalists, Rakhine parliamentarians campaigned hard for the ethnic Rakhine statehood where they would have the lion’s share of the administrative and political powers while Muslim Rohingya politicians in the national parliament struggled to get their group’s share in state power.

Importantly, the Rohingyas were not prepared to be placed under the administrative domination under ethno-nationalist Buddhist Rakhine with whom they had bloody communal feuds during WWII, in the anticipated autonomous Rakhine state, thanks to the weapons acquired from occupying Japanese and the exiting British. Rohingya leaders therefore openly sided with the central government and the military – both in the hands of the ethnically Bama or Burmese politicians and generals.12

However, Rohingya politicians and community leaders knew that they were between rock and the hard place.

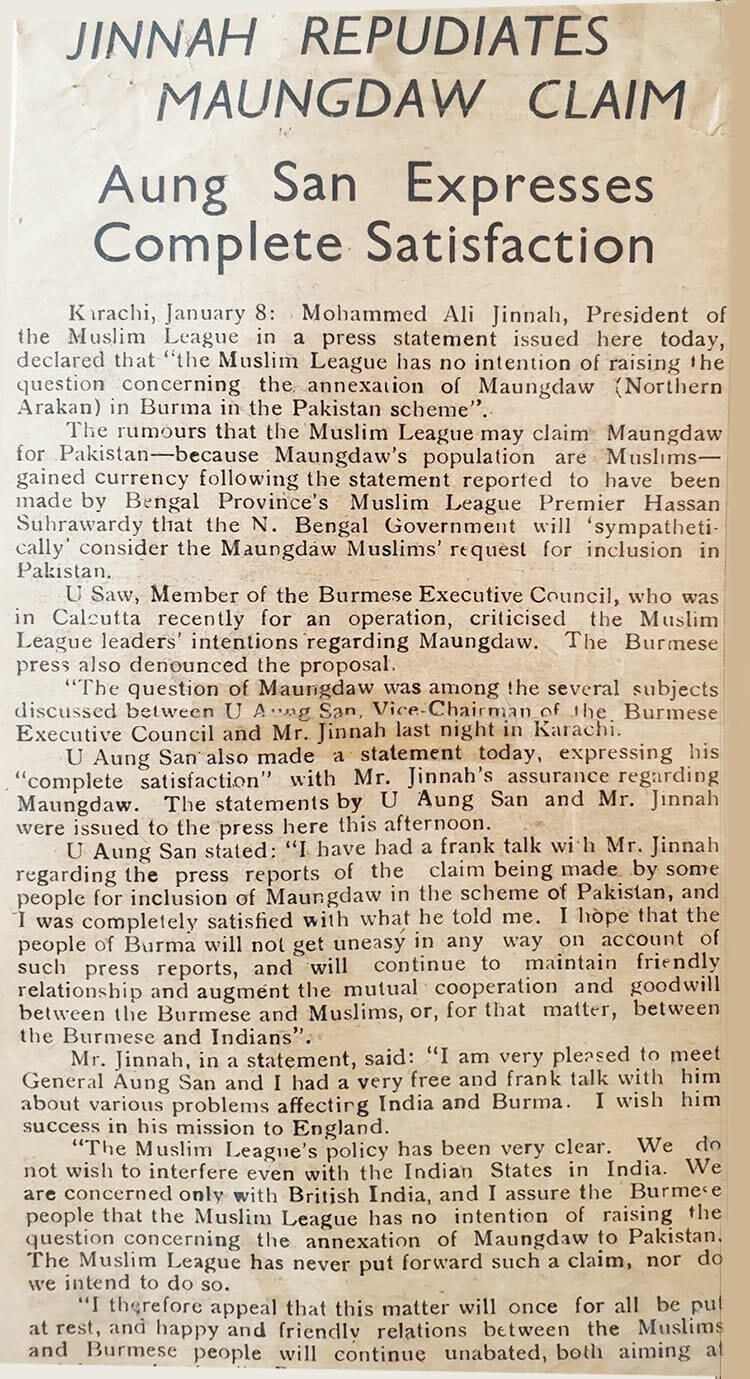

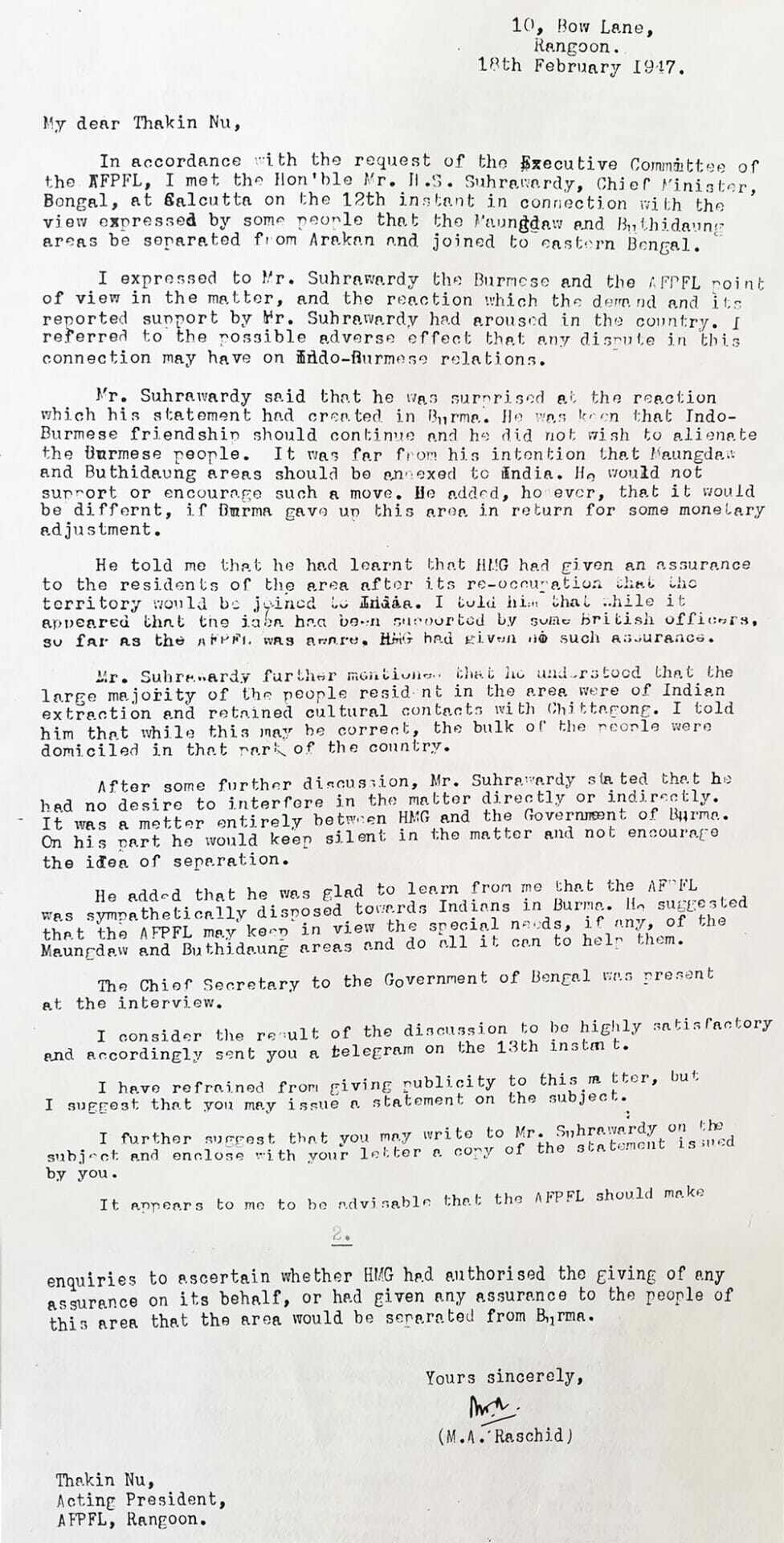

The idea of secession of Muslim Rohingya with the view towards joining up with the adjacent predominantly Muslim republic of (East and West) Pakistan was a pipedream. Neither the pre-partition Muslim leaders such as Mohammad Ali Jinnah, nor the Bengal chief minister, H.S. Suhrawady, Esq. who had administrative control over the then East Bengal, were sympathetic to any secession aspirations of the sizable Muslim population of Western Burma.

After his meeting with the nationalist leader General Aung San in Karachi on 8 January 1947, Jinnah issued the official statement “the Muslim League had no intention of raising the question regarding the annexation of Maung Daw (Northern Arakan) in Burma in the Pakistan Scheme.”

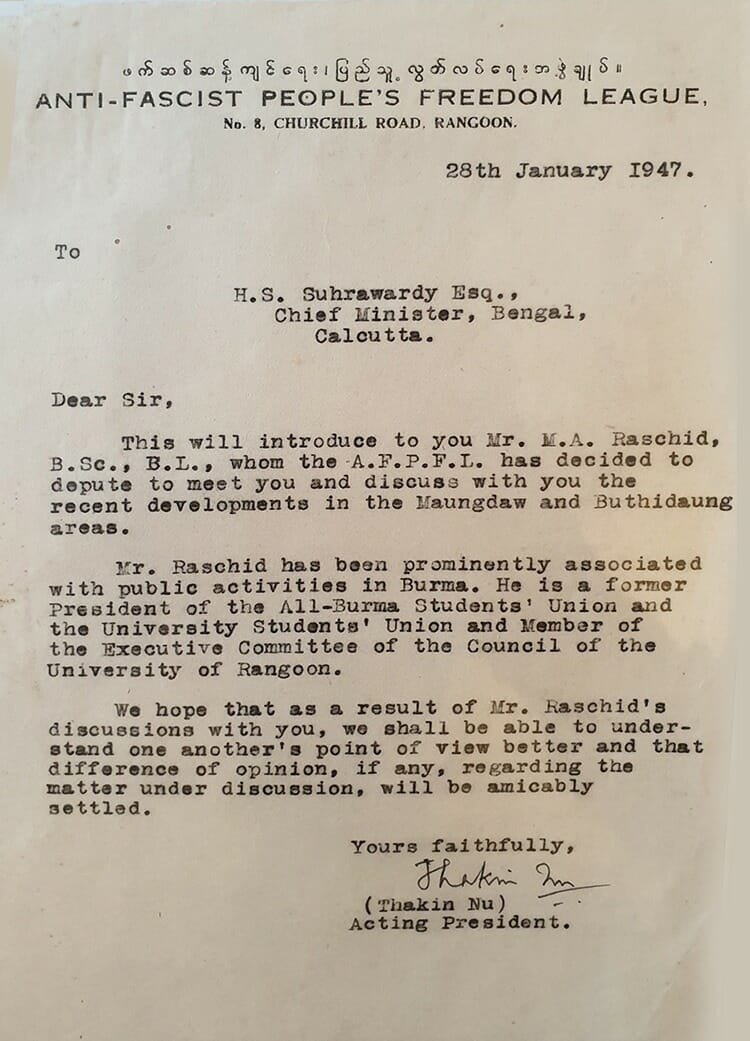

See the inserted photographic copy of a sample news report dated 8 January 1947, followed by the copies of the official correspondence to the Bengal chief minister, H.S. Suhrawady, Esq. by U Nu, Aung San’s deputy, who after the latter’s assassination in July the same year, became the leader of Burma. While Aung San was on official visits to the pre-partition India and United Kingdom in preparations for Burma’s independence, Nu was serving as Acting President of the pre-independence nationalist organization Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League or AFPFL dated 28 January 1947. Also, it is worth reading M.A. Rashid’s report regarding his meeting with the Bengal Chief minister specifically to seek clarifications regarding the rumoured annexation of Northern Arakan into India upon independence. These materials – originals – are in the personal collection of Bilal Rashid, the oldest son of the late MA Rashid, who resides in Maryland, USA. In November 2019 I photographed them with Bilal Rashid’s permission.

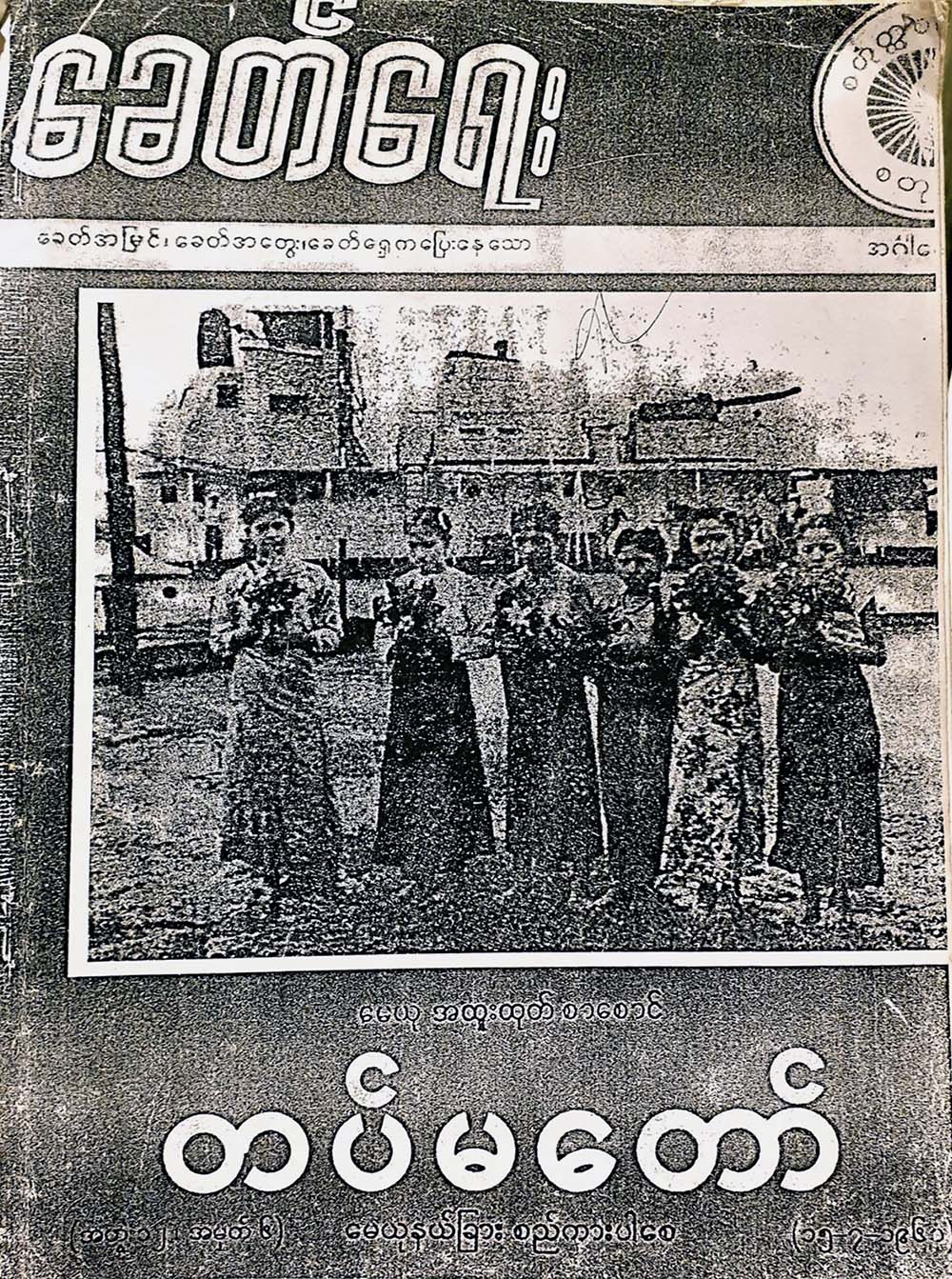

One of numerous publications, printed materials and on-line posts which propagates the false view that “Bengali” were invaders across the Western gate” into Fortress Myanmar. This one is entitled “The War Against Land Grab at Western Gate” (the second printing, February 2017, 6 months prior to the genocidal purge of over 740,000 Rohingyas. The victims were Rakhine Buddhists who had been portrayed as “helpless” in the face of illegal Muslims from across the border in Bangladesh.

Historical evidence therefore offers no empirical basis for the official fear or the popular imagination of “Muslims of Northern Rakhine”, taking a slice of “Buddhist land” and joining up with Bangladesh.

Local concerns and communal tensions among the two major ethnic blocs – Rakhine and Rohingya – have been systematically stoked by the successive military regimes and local anti-Rohingya and anti-Muslim nationalists among the predominantly Buddhist Rakhines.

From the perspective of the dominant Bama, both civilian and military elite, centred in Rangoon, both groups were “trouble-makers”.

The painful fact is this: Bama elites liked neither Rakhine Buddhists – because of their staunch anti-Bama ethnonationalism, however justified – nor the Rohingyas – because they are predominantly Muslims and with bicultural and common religious ties to the Muslims of neighbouring East Pakistan (and later Bangladesh).13

On the eve of the NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi travelling to The Hague in December 2019 in order to defend and deny the allegations of genocide against the Rohingya by the State of Myanmar in the Gambia vs Myanmar case at the International Court of Justice, gigantic billboards were erected in Rangoon and the rallies in support of the joint legal and public relations defence by the civilian government of Aung San Suu Kyi and the military were held across different cities and towns in Myanmar.

Administrative Divisions of Rohingya and Rakhine – With Bama Military as the Referee

Out of this triangular ethno-religious politics emerges the shifty strategic games played by political elites of all three groups, with divergent and conflicting political and strategic agendas. As is the case with any colonial divide-and-rule politics, the central colonising ethnic bloc, particularly the Burmese military, have played Rohingya Muslims against Rakhine Buddhists.

In the 1950’s, the Burmese military – led by General Ne Win as the Commander-in-chief – practically controlled all restive border regions vis-à-vis civilian administrations of non-Burmese ethnic groups. To the chagrin of Rakhine nationalists who wanted to keep Rakhine as one autonomous region, under their control, the Ministry of Defence Division of Border Affairs approved the Rohingyas’ demands for a predominantly Muslim administrative district called Mayu District – made up of the two northern Rakhine townships of Maungdaw and Buthidaung, as well as parts of Yathaydaung township, something Prime Minister U Nu’s civilian government rubber-stamped.

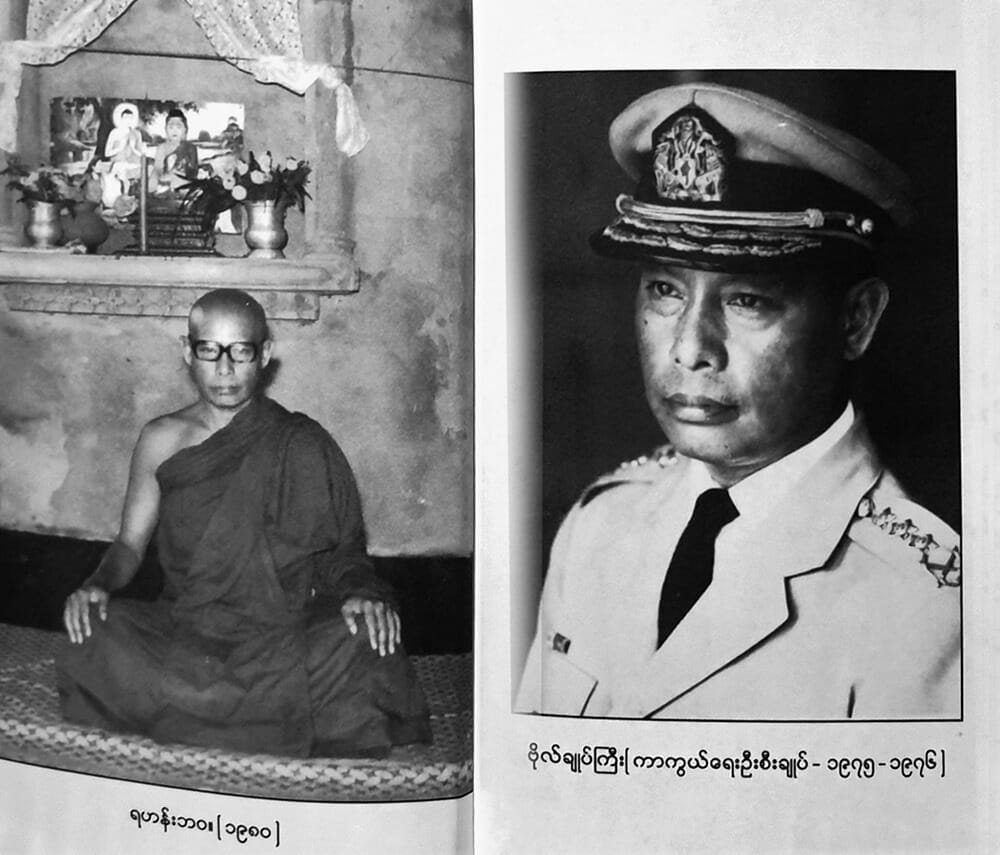

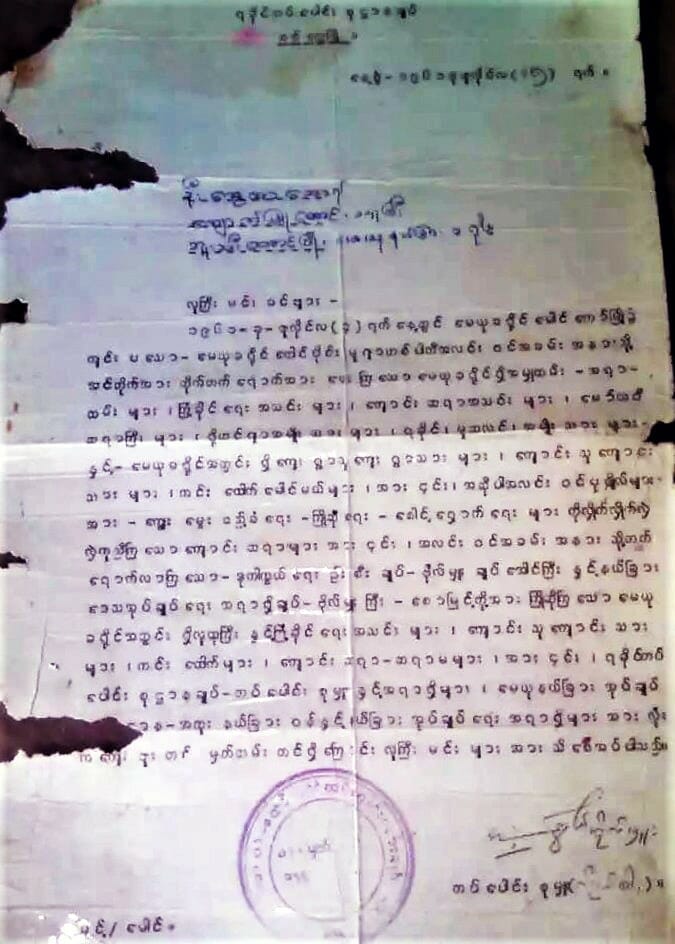

The following pictures – the cropped passages from the Ministry of Defence Publication Khit Yay of Current Affairs, dated 15 July 1961 – serve as the official proof of the operationalization of the Mayu District Administration, named after Mayu River. It stated that the new administration was effectively operational on 30 May 1961. It comprised of the two predominantly Rohingya townships of Buthidaung and Maung Daw and parts of Rathaydaung township. The commander and deputy commander – Lt-Colonel Ye Gaung and Major Ant Kywe (my late great-uncle) – were in charge of all matters concerning Northern Rakhine’s Rohingya populations.

As a matter of fact, the Administration was established as early as mid-1950’s under the then commander of All Rakhine Commands named Lt-Colonel Tin Oo (now the ailing Vice-Chair of NLD party and ex-General Tin Oo, former who served as Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces under Chairman Ne Win of the Burma Socialist Programme Party, one party military dictatorship).

However, it was not operational owing to the Burmese military’s inability to bring N. Rakhine under its effective control. With the surrender of 290 – one of the largest batches – of Mujahideen fighters from Rohingya community in July 1961, the Burmese military, under the (nominal/ritual) approval of civilian government of Prime Minister U Nu, the military began to run the Mayu District Administration.

Rather dishonestly, in one of the Radio Free Asia Burmese Service interviews, NLD leader Tin Oo denied that Rohingyas existed as an officially state-recognized ethnic group integral to the Union of Burma, despite his first-hand knowledge of the group’s presence, culture, identity with all the features of all borderland ethnic communities with links to both new nation-states of East Pakistan (and since 1971 Bangladesh) and Burma (and since 1989 Myanmar). In his two-volume authorized biography written by Sein Tin, the then All Rakhine Command Commander Tin Oo talked about how he led the attempt, at gun-point, to drive out “illegal East Pakistanis” after a thorough immigration checks. Only a few hundreds were found to have no proof of documentation to reside in Burma.14

Myanmar State’s Official Recognition of Rohingya as Integral Indigenous Ethnic Group of the Union of Burma

Noteworthy is the fact that the senior most leadership of the Burmese military officially consented to the Rohingyas’ right to self-identify as Rohingya ethnic nationality and, additionally, recognised the group as a constitutive and integral ethnic group native to Western Myanmar. There exists a mountain of both primary and official documentations that support Rohingya group identity and history of belonginess in Northern Rakhine.

See the verbatim Burmese language transcript of the address delivered by General Ne Win’s second-in-command, Brigadier General Aung Gyi, at the Mujahideen surrender ceremony held in Maung Daw Town, 4 July 1961.

In his own published writings, the late Deputy Commander-in-Chief Brigadier Aung Gyi, General Ne Win’s second in command, recorded the Ministry of Defence discussions with Rohingya leaders, which were designed to bring an end to the lingering Mujahideen armed rebellion.

A crucial agenda item in these discussions included acknowledging Rohingyas’ minority group rights to self-identify as Rohingya – and, specifically, NOT to be lumped under the religious label of “Muslims of Rakhine”.

Major Ant Kywe, (circa. 1960)

The late Lt-Colonel Ant Kywe, – my late grandfather’s younger brother – served (in 1959-1962) as the Deputy Commander of All Rakhine Command headquartered in Sittwe and concurrently assumed the deputy-chief of the newly established and operational Mayu District Administration. His own type-written and signed official Thank You note to all Rohingya community and religious leaders, teachers and other civil servants who assisted the Ministry of Defence to make the surrender ceremony of the last batch of 200-strong Mujahideen fighters a success, addressed Rohingyas as “esteemed Rohingya leaders and Rohingya people.”

(See the inserted authentic copy of this official Thank You letter by Major Ant Khwe, my late great-uncle deputy Commander of All Rakhine Command, 1961 here: https://www.maungzarni.net/en/news/rohingya-ethnic-nationality.)

Official type-written “Thank you” letter to Rohingya community leaders signed by Dy-Commander of All Rakhine Command, Major Ant Kywe

So, when Arakan Army Chief Tun Mrat Naing told Prothom, “(w)e refer to them as the ‘Muslim inhabitants of Rakhine,” he is setting the political clock of Rakhine state back to the 1950’s.

So, when Arakan Army Chief Tun Mrat Naing told Prothom, “(w)e refer to them as the ‘Muslim inhabitants of Rakhine,” he is setting the political clock of Rakhine state back to the 1950’s.

He also repeated the fact that the Arakan Army has made efforts to recruit and include some members of this “Muslim inhabitants” into the Arakan Army’s police and local administrative units.

Considering the fact that Rohingyas were a key stakeholder – they are the largest ethnic bloc after Buddhist Rakhine who outnumber them 3:1 before the last wave of the genocidal purge – talk of making Rohingya policemen and local administrators does not sound visionary befitting an aspiring national leader. Even if one were to erase the well-documented important role played by Calcutta- and Rangoon-educated Rohingya leaders such as Abu Gafur, Sultan Ahmad and so on, who had served in General Aung San’s pre-independence Constituent Assembly, alongside Rakhine politicians, helped draft the original Constitution of the Union of Burma, served in the post-independence cabinet of Prime Minister U Nu, sat in the national parliament, Tun Mrat Naing’s talk of the Rohingya’s roles as simply low level law enforcement agents set up by Arakan Army leadership only adds insults to the genocidal injury of Rohingyas, in Myanmar and in diaspora worldwide.

Rakhine Nationalists as Collaborators in Rohingya Genocide

Importantly, Tun Mrat Naing chose not to acknowledge the collaborator role that thousands of Rakhine nationalists have played in the Burmese military’s institutionalised genocidal persecution of Rohingyas since February 1979. While the spearhead of the genocidal purges has typically been the Burmese military troops (and other security agencies such as the Border Guards, police and riot-controlled military-police hybrid units called Lon-htein), anti-Rohingya local Rakhine nationalists had played instrumental roles in virtually all waves of genocidal attacks on Rohingya communities.

As a matter of fact, the two anti-Rohingya Rakhine nationalists the late historian Dr Aye Kyaw – a friend of mine – and high education director general the late San Thar Aung were key drafters of the 1982 Citizenship Act which became the legal weapon of genocide, stripping virtually all Rohingyas of citizenship and the right to belonging in Burma. The “purity of blood” discourse of this citizenship had the echoes of the Nuremberg Race Laws passed as major decrees by the Nazi Party in 1938, which by default rendered statelessness (that is, no legal rights, no protection, no access to any support from the state, no right to travel, beyond the confines of designated areas, ghettos and camps) any group that was not deemed “pure blooded German”.

Chairman Ne Win of the Burma Socialist Programme Party addressed the meeting held in his presidential palace announcing the plan to introduce the new hierarchy of New Citizenships based on “purity of blood” as native ethnicities of Burma, the frontpage story from the Working People’s Daily (State’s bi-lingual mouthpiece), 9 October 1982.

In their 15-October-2021-dated book review entitled “The Statelessness Pandemic”, published in Project Syndicate, Laura Van Waas and Natalie Brinham of the Institute on the Stateless and Inclusion called world’s attention to the chilling linkages between citizenship stripping and genocides.

They write, “the rise of fascism in the 1930s and 1940s further exposed the fallibility of this system and the ominous reality of the state’s power to exclude people or strip them of citizenship. Across Europe, citizenship-stripping went hand in hand with genocide for Jews and other minority groups.”

Van Waas and Brinham continued, “… statelessness remains a key causal factor in human-rights abuses. The international community has come under scrutiny for failing to protect Myanmar’s Rohingyas from mass atrocities. But the writing there had been on the wall since the enactment of the country’s 1982 citizenship law, which stripped them of their rights.”

In the two bouts of “communal violence” in June and October 2012, which resulted in the displacement of over 100,000 Rohingyas – still caged in Internally Displaced Persons camps in central Rakhine state after nearly a decade – organised armed Rakhine led the killings and destruction of Rohingyas and other Muslims with different ethnicities such as Kaman and Myanmar, with complete impunity from the Burmese government of President Thein Sein (2010-15).

In addition to the earlier waves of genocidal purges, Rohingyas had by 1982 been made the group that did not belong to Myanmar, hence entitled to no protection from the state. The 1982 Citizenship Act, really a decree ala Nazi Party’s Nuremberg Race Laws by one-party dictatorship of Chairman Ne Win, had well served the “democratizing state” under the reformist general-cum-President as an effective “legal” instrument of genocide.15

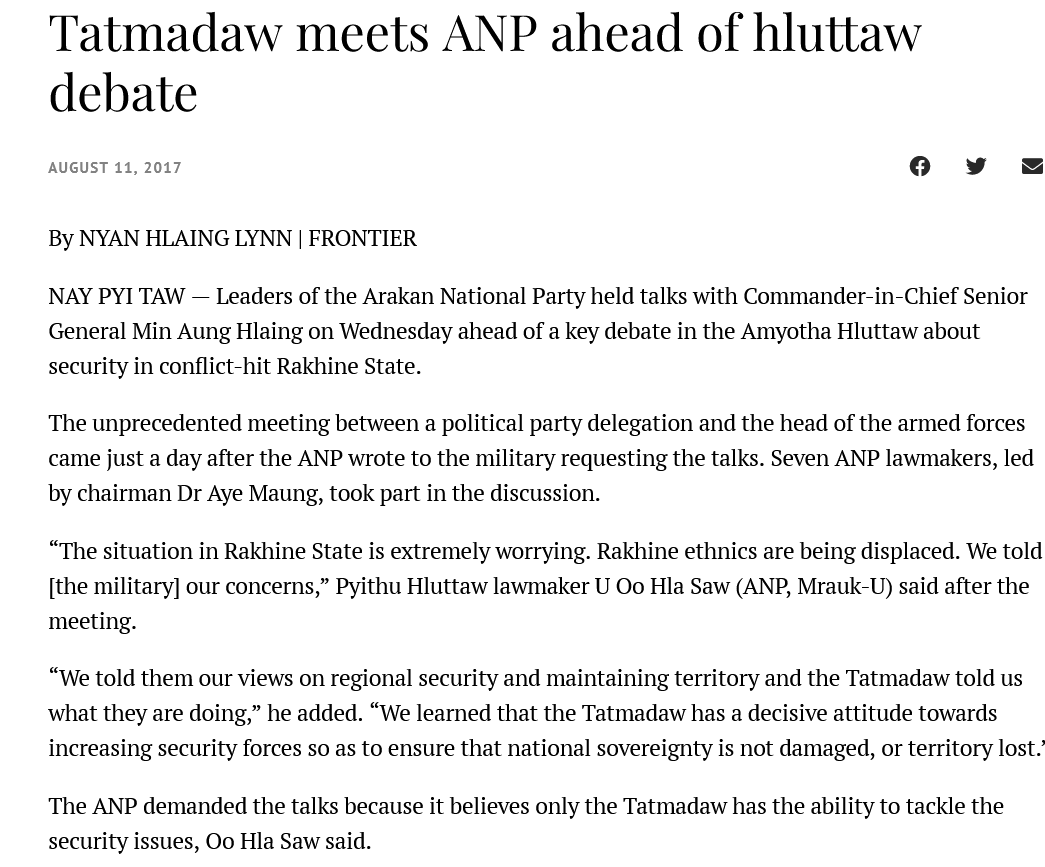

Additionally, it was a group of most prominent Rakhine nationalist politicians in the national parliament in Naypyidaw, including vet Dr Aye Maung and teacher-cum-MP Oo Oo Hla Saw who publicly and officially met and “requested” Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing to send “troops” in order to protect Rakhine Buddhists from the threats of “Muslim terrorists”, on the eve of the largest genocidal purge in Burma’s history.16

Myanmar military leadership happily obliged and launched “security clearance operations” in August 2017, having destroyed, according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum researchers, over 38,000 physical structures including mosques, homes, schools, clinics, rice warehouses, and shops, slaughtering thousands of “Muslims of Rakhine”, and mass-rape of Rohingya women. Consequently, nearly 800,000 survivors fled into Bangladesh, in a span of several months.

The rest is history as they say.

In addition to these glaring omissions and refusal to acknowledge Rakhine nationalists’ collaboration in the Burmese army’s genocide against the Rohingyas, Arakan Army leader displayed a disturbing lack of understanding and appreciation of a crucial element in all genocides.

Erasure of Identity and History as an Integral Component of Genocide

The desire for and intentional attempts at erasing the history and group identity of the targeted community is central and common across all documented cases of genocide, from the Turkish genocide of the Armenians one hundred years ago to Nazi genocide of the Jewish people, Roma, Russian, Poles and Sinti, as well as in the Bengali genocide by the West Pakistani army in 1971 and Rwanda and Bosnian genocides of the mid-1990’s.

While talking about his respect for “human rights and citizenship rights of the Muslims of Rakhine state” he obviously did not know that the apparent refusal to accept the well-documented Rohingya history and identity is in breach of the rights of Rohingya to self-identify.

Worse still, the kind of speech act falls within the realm of genocidal discourse.

The victims, typically a vulnerable group, are never allowed to self-identify. Nor do the perpetrating group ever acknowledge and accept the victims’ group identity. It is crucial to note that in the case of Rohingya the acts of killing and destruction have been carried out by both the Burmese military and Rakhine collaborators.

As the father of genocide studies, the late Polish-Jewish scholar Rafael Lemkin pointed out clearly perpetrators typically impose their preferred or chosen national patterns on the victim groups.17

Hence, “No Rohingya”, but only “Muslims of Rakhine state” in the Rakhine nationalist discourses. Tun Mrat Naing merely repeated this popular genocidal narrative.

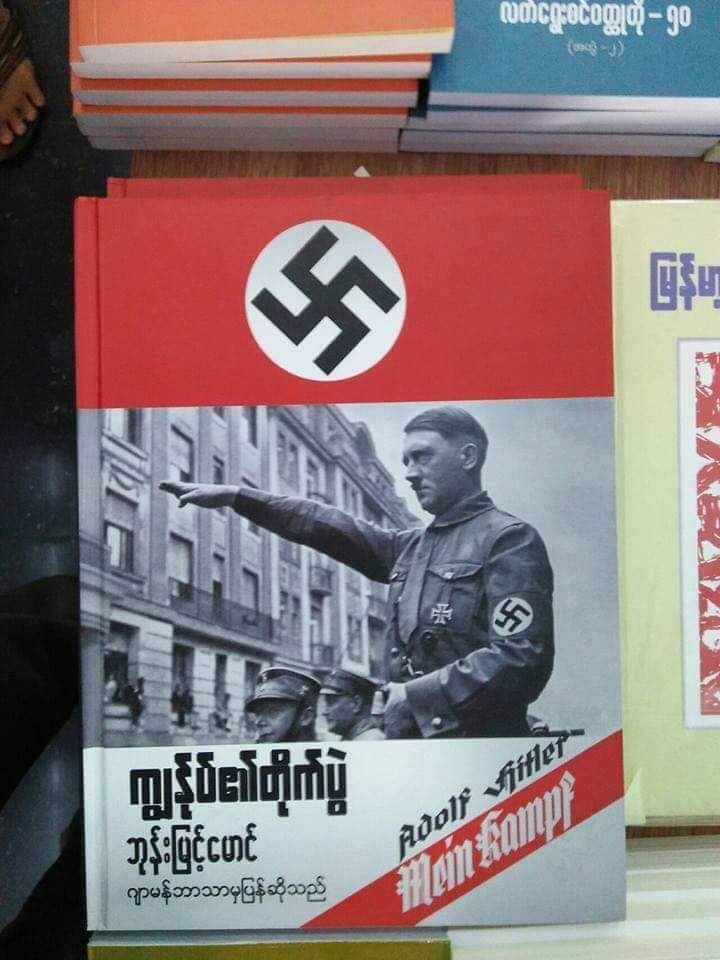

Copies of the Burmese translation (from German) of Mein Kampf, Nazi’s “bible”, seen on the shelves of a bookstore in Yangon, in 2017, the year of the largest genocidal purge.

In the midst of different waves of “communal violence” of 2012, Rakhine nationalists have openly stated that Israel is their inspirational model. More troublingly, ominously, Rakhine dissidents in Thai-Burmese border town of Mae Sot are known to keep copies of Hitler’s Mein Kampf and in Rakhine publications Hitler and Nazis have been painted as “patriots who did the needful in the German nation’s interests.”

Furthermore, Rohingyas are a borderlands, bi-nation-state people.18 Typically, there are found two different names for villages or places, and peoples. Examples near and far abound. Poles and Ukranians in the pre-World War Eastern Europe, Jing Hpaws or Sing Hpaw of Northern Myanmar state of Kachin on the Sino-Burmese borders, Dai or Shan along Thai-Burmese-Indian borders, Chin or Zo along Indo-Burmese border provinces, and Mon and Karen along Thai-Burmese borders spring to mind.

As a matter of fact, both Rakhine and Rohingya communities exist on both sides of Bangladesh-Myanmar border. Rakhines in Bangladesh side are allowed to keep their Buddhist and ethnic identities, and Bangladesh is not worried about Bengali Rakhine joining hands with Rakhine in Myanmar to fight for secession. Not only do the Bengali Rakhine have full citizenship rights and keep their Rakhine identity openly do they have opportunities to serve the state in Bangladesh with dignity. I even met a Rakhine official, a Bengali who served as an executive assistant to the Speaker of Bangladeshi national parliament Dr Shirin Sharmin Chaudury in her office in July 2018.

NLD leaders including Aung San Suu Kyi, successive military leaderships since the 1982 Citizenship Act’s passage and Rakhine scholars, politicians and community leaders were all behind the international and nation-wide propaganda campaign that spread the malicious – and genocidal – idea that Rohingyas are a “fake ethnicity”. Aung San Suu Kyi officially and blatantly told the international diplomats, politicians and INGOs not to use the “emotive” word ‘Rohingya’.19

Genocidal Historiograpies of Rakhine and Burmese Nationalists

At about the time the NLD leader appeared at the International Court of Justice to deny and defence the allegations of genocide in The Gambia vs Myanmar case in December 2019, her Minister for International Cooperation told the Voice of American Burmese Service that the main objection behind calling Rohingya by their ethnic group name is the concern that Rohingya will demand a separate state, as an ethnic group, hence the relentless and official attempts to falsely presenting the Rohingyas a “fake people”.

This act of projecting the perpetrators’ unfounded and groundless fear onto the targeted vulnerable group is known as an act of “mirroring”: genocidal killers looking at the targeted group of people – ethnic, racial, national and religious – and deluding themselves that the group they are looking at have intentions to kill and commit genocide (against the dominant groups).

It is worth noting the concept that emerged out of Rwanda genocide. According to the Wiki entry “incitement to genocide”,

“(a)ccusation in a mirror” is a false claim that accuses the target of something that the perpetrator is doing or intends to do. The name was coined by an anonymous Rwandan propagandist in Note Relative à la Propagande d’Expansion et de Recrutement. Drawing on the ideas of Joseph Goebbels and Vladimir Lenin, he instructed colleagues to “impute to enemies exactly what they and their own party are planning to do.” By invoking collective self-defense, propaganda justifies genocide, just as self-defense is a defense for individual homicide. Susan Benesch remarked that while dehumanization “makes genocide seem acceptable”, accusation in a mirror makes it seem necessary.20 (emphasis added)

The view that Rohingya did not exist or the term was never used before 1950’s collapses in the face of multiple sources of primary historical documents. Even GH Luce, the founder of historical studies of Burma and his most prominent student the late Than Tun intimated that Rohingya identity and presence date back to 15th century.

The truth is this.

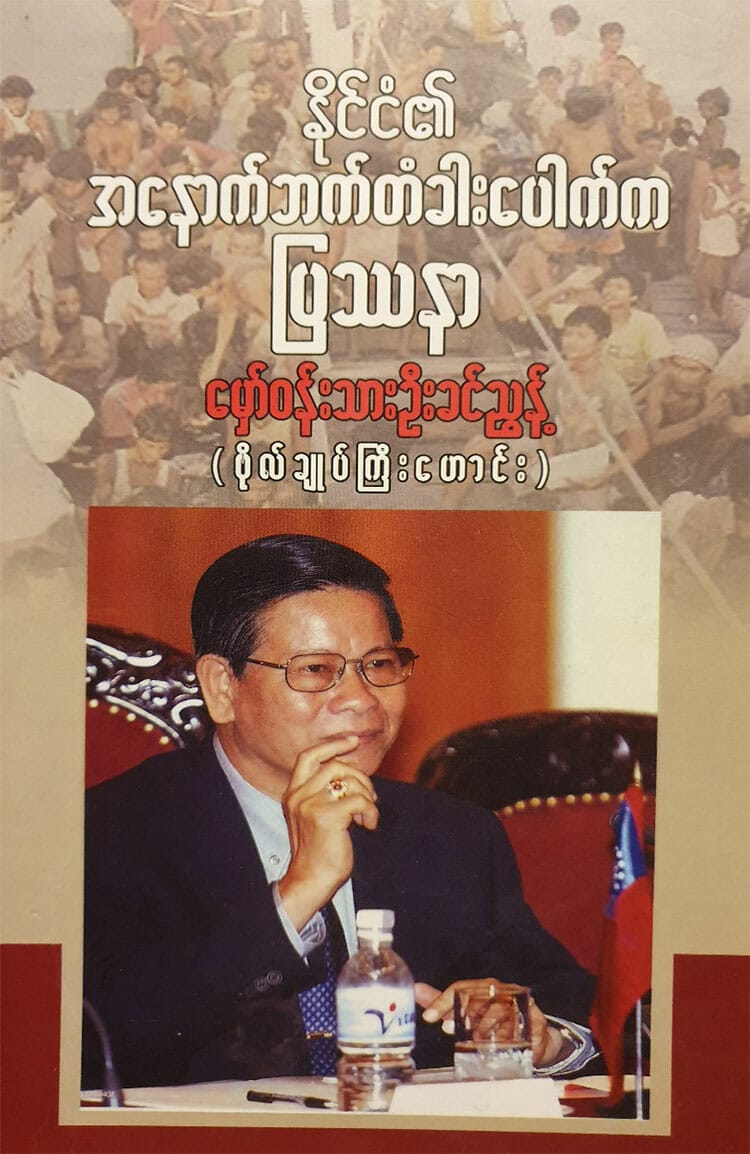

Front cover of ex-military intelligence chief ex-General Khin Nyunt’s collection of essays entitled The Problem or Threat at Our Nation’s Western Gate (Yangon, 2016).

For 500 years Rakhine and Rohingya have inter-mingled, culturally, demographically, administratively and commercially, both deeply and more influenced by what Michael W Charney, the leading historian of ancient Arakan at the School of Oriental and African Studies, calls the Bay of Bengal civilisation of Eastern India. For they were geographically and culturally isolated from the Dry Zone Buddhist civilisation, and political centres which came to form the dominant pillar of post-independence Burma.

Tragically, Rakhine nationalists have been engaged in the acts of purifying their past, erasing any presence or role of Rohingyas and other groups in the rise of Rakhine kingdom.

This was in synch with the Burmese military intelligence’ s genocidal project as spelled out by Gen. Khin Nyunt in his various publications including a monograph entitled “The Problem or Threat at Our Nation’s Western Gate” (Yangon, 2016). In this nationalist revisionist history Rakhine was “a purely Buddhist land”, like Myanmar as a whole was. The Rakhine and Burmese histories have been distorted to fit the present nationalist vision of the “Buddhist and feudal” as opposed to secular and modern – military.

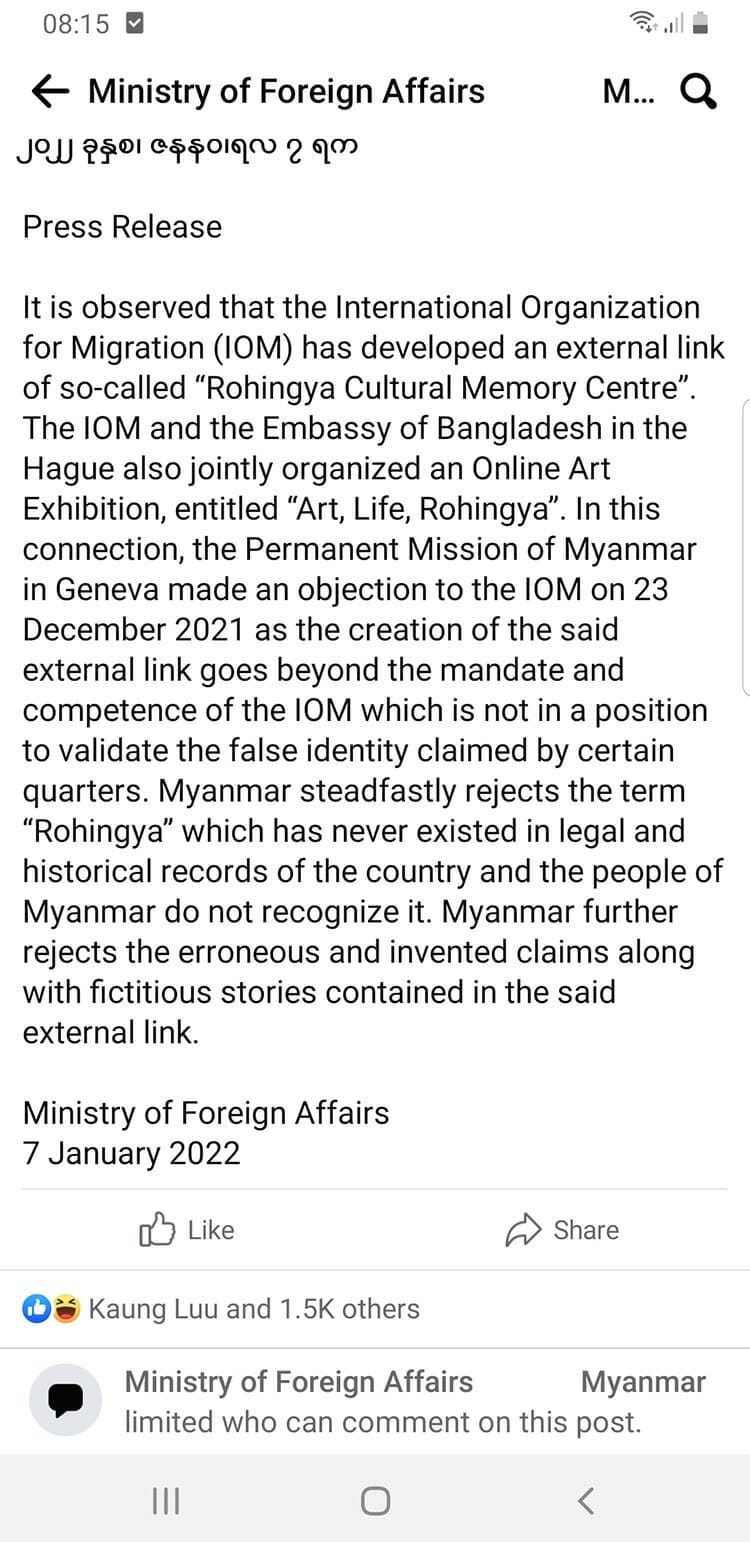

More recently, five days after Rakhine nationalist’s Prothom Alo interviewed was published Myanmar military regime issued an official protest letter (dated 7 January) – posted on its official Ministry of Foreign Affairs website – against the International Organization of Migration (IOM)’s usage of the ethnic name Rohingya on the latter’s website.

Against all evidence to the contrary, the official letter repeats its tired, old and non-credible assertion, “the term ‘Rohingya’ has always been rejected by the Burmese people and is not recognized by the Burmese people. Myanmar has also rejected the false and misleading statements and information contained on the website.”21 From where I sit the genocidal military regime of Min Aung Hlaing knows it has zero credibility with neither the United Nations – which has effectively refused seat its representative at the United Nations in 2021 and 2022 – nor the wider international audiences. The statement therefore appears to be designed to placate specifically Rakhine nationalist public, which have chosen to stay out of the violent and non-violent resistance movement across all other ethnic regions of the country.

Facts don’t matter to nationalists, insofar as histories, identities or empirical realities which concern them.

Facts don’t matter to nationalists, insofar as histories, identities or empirical realities which concern them.

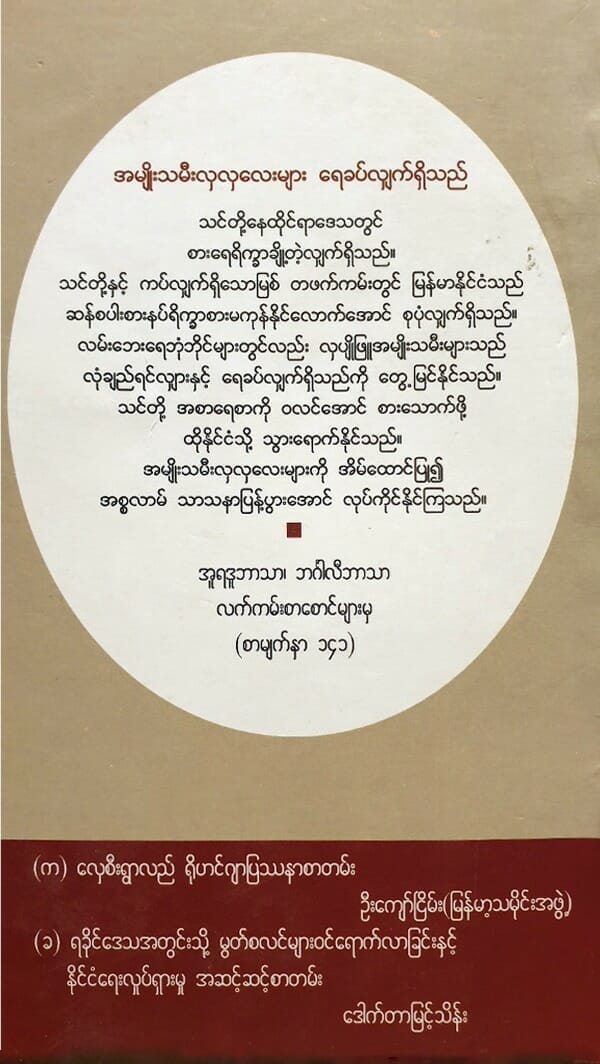

The back cover of ex-General Khin Nyunt’s book contains the lines that essential enticed the wretched of East Bengal to cross over to Myanmar where they can access ample supplies of food, fair-skinned Burmese belles, in their half-clad longyi, showing their bosoms, whom they can marry and launch their “love jihad” of Islamicisation of the locals. These lines were purported to have been translated from the pamphlets and poems written in Urdu and Bengali and circulated in (East Pakistan and later Bangladesh).

Myanmar’s Buddhism was a foreign implant from ancient India, and “Buddhist peoples” and “Buddhist way of life” were invented after Buddhism arrival. From the Buddhist nationalists’ standpoint, the country has been “invaded” by Islam and those dark-skinned people who arrive, unwelcome, from the Indian sub-continent.

Tun Mrat Naing’s apparent concern that Rohingya group identity and history in Rakhine displace and make invisible Rakhine Buddhist’s own ethnonationalist history and dilute Arakan identity is misguided. For unlike Rakhine nationalist historical narratives, Rohingyas and those of us who have come to support both minority/group and human rights of Rohingyas never claim Rakhine or Arakan to be exclusively for the predominantly Muslim Rohingyas.

Misguidedly, the Arakan Army leader Tun Mrat Naing dismisses the western-educated Rohingya in the diaspora, as, in effect, un-worthy or unquailed as Rakhine’s partners in post-genocide reconstruction in “Rakhita”, either as an internally sovereign state or an independent republic. With almost no exception, this category of Rohingya – who have come to serve as the faces and voices of the Rohingya genocide victims globally, have repeatedly stressed the fraternal ties with Rakhine Buddhists. They have offered to cooperate fully as co-equals who share the ancient Arakan as their ancestral birthplace. Thanks to their genuine offer of reconciliation and solidarity with the other oppressed groups of Myanmar they have won the hearts and minds of the Bama majority since the February coup and the bloody crackdown of peaceful protesters last year.

Genocidal Crimes as One-Sided, State-Backed Destruction of an Identity-Based Group

Importantly, Rohingyas have not attempted to erase the Buddhist tradition or ethnic Rakhine presence. The cleansing of Arakan’s history along religious and ethnic lines has been carried out only by the likes of Burmese military leaders and their collaborating Rakhine nationalists.22

The term “Arakan or Araccan” refers to the inhabitants of the kingdom known as Arakan. It has no religious or ethnic connotations, neither Buddhist nor Muslims, neither Rakhine nor Rohingya.

It is the Rakhine Buddhists who have usurped the term “Arakan” as in Arakan Army (which is effectively the Rakhine Buddhist liberation army) and its political party, the United League of Arakan, and deprived Rohingyas of their rightful belongingness to the shared birthplace.

In this, Rakhine nationalists are no more progressive nor more enlightened than the Burmese military regime with whom they share the single cancer of Islamophobia. I know that Tun Mrat Naing’s liberally-tongued interview has disappointed many a Rohingyas – and some are outraged and insulted – as the Rakhine nationalist continues with the genocidal erasure of Rohingya’s history and identity while trampling on the rights of Rohingya – a protected group under the Genocide Convention – to self-identify, with or without needing any organization’s approval, Arakan Army or the genocidal State of Myanmar.

As an anti-colonial Bama – a former Myanmar military cadet admit (in 1980) at that – I had welcomed, supported and in a few cases, facilitated, the Rakhine-Rohingya reconciliation talks, public and private, involving Arakan Army supporters and a handful of Western educated Rohingya campaigners in diaspora, before the military coup a year ago. I personally feel let down by the rather regressive views that a very important Rakhine leader has aired through his 2 January-dated Prothom Alo interview – and the continuing blatant disregard the Arakan Army has shown towards the Rohingya’s group right to self-identify as Rohingya.

History is full of painful ironies.

In her special message of solidarity pre-recorded for the Free Rohingya Coalition International Conference on Rohingya genocide held at Barnard College/Columbia University in February 2019, the renowned Black Feminist intellectual & Professor Emerita Angela Davis of the University of California at Santa Cruz identified the deeply ironic but recurring phenomenon where the formerly persecuted groups morphing into the persecuting group themselves once they are in power.

As a Burmese, I hope that General Tun Mrat Naing will meditate on the misguided and dangerously genocidal views he and his followers have evidently held towards the only ethnic community of Myanmar which does not have a real armed revolutionary organization, to pose any security threat to anyone, Rakhine or the country at large.

The 17th Sept.-dated official statement by the United League for Arakan, the political wing of the Arakan Army, continues to address Rohingyas as “Muslims” in blatant & official breach of Rohingya’s right to self-identify, to the dismay & outrage of Rohingya genocide survivors. But it addresses its own Buddhist community by its chosen ethnic name “Rakhine”, and conceals the Rakhine’s toxic ultra-Buddhist ideology.

The 17th Sept.-dated official statement by the United League for Arakan, the political wing of the Arakan Army

All genocides involve group identity destruction where perpetrators impose their design or preferences on the victims’/survivors’ community, according to the late Rafael Lemkin who fathered the term “genocide” (or intentional identity-based destruction).

Maung Zarni

Banner image from Tweet below – https://twitter.com/shafiur

- Tun Mrat Naing Interview.

- Wunna Kyaw Htin Zan Yin was his name, with Wunna Kyaw Htin being the highest state honour for civil servants, the (neo-feudal) tradition of which began during the first parliamentary democratic rule of Prime Minister U Nu (1948-62) . Before his retirement in the late 1970’s Zan Yin was a member of the elite Burma Civil Service, and held the post of the Commissioner of Sagging Division, on the west bank of the Irrawaddy River across from Mandalay.

- Zeya Kyaw Htin Lt.-Colonel Ant Kyaw was his name, with Zeya Kyaw Htin being again a neo-feudal title awarded to senior ranking commanders. He was originally with the Burma Rifle Brigade #1, and rose through the ranks to become the deputy commander of All Rakhine Command in 1959, and was one of the 100 senior commanders who endorsed General Ne Win’s coup of 1962, which ended the parliamentary democracy and instituted the military dictatorship. Than Shwe served as a young officer in his Burma Rifles Brigade Number One in the early 1950’s.

- My late uncle was Major Hpone Maung was the only Defence Service Academy graduate from the In-take-6, graduating class of 1963 (out of the total of 30 officers)., who was “wing-ed” in the Burma Air Force in 1964 In addition to General Ne Win’s VIP pilot, he also served as a General Staff Grade – 3 officer at the Directorate of Military Training, who drew up the blue print for the new officer cadet school named “Officers Training Corp” . The current Deputy Commander-in-Chief (Air Force) Lt-General Maung Maung Kyaw is an early graduate of this program, and so is the highestranking hand-picked Member of the Parliament, a Brigadier, at Myanmar national Parliament where the military was allotted 25% constitutionally guaranteed seats vis-à-vis open civilian electoral process.

- The late General Ne Win had the longest reign as the official and later un-official Number One (General) since he replaced the Sandhurst-trained professional solider General Smith Dunn in February 1949 in the midst of the Karen National Defence Organization’s insurrections against the Prime Minister U Nu’s multi-ethnic government. Of the 26 Burmese nationalists patronized and trained by Japan’s Fascist military, as the nucleus of the Burma Independence Army with Aung San as its head, Ne Win was one of the 3, that were given special training at the Nakano Academy of Military Intelligence. This school was known as Kempeitai School, was Japan’s hybrid between Nazi SS and Gestapo, and dismantled after Japan’s unconditional surrender in August 1945. General Ne Win’s command of the Burmese armed forces was unchallenged and unchallengeable and effectively lasted from February 1949 till he resigned in July 1988. He single-handedly moulded the ideological orientation of the Burmese armed forces along the neo-Fascist, Kempeitai model – as opposed to the militaries in democratic systems. For the first-person detailed accounts of the so-called Thirty Comrades – the nucleus of the Burma Army – their training by Fascist Japan’s Imperial Military and the power struggles within the post-independence Burma Armed Forces, see (Retired) Brigadier Kyaw Zaw (2007) My Memoirs: From Hsai Su to Meng Hai, (Hyattsville, MD: USA).

- Audiotaped interviews with (Retd) Colonel Chit Myaing, Sterling, Virginia, Fall 1994 (in my collection).

- Ibid.

- Tun Mrat Naing Interview, 2 January 2022.

- U Kyaw Min – known popularly as ICS U Kyaw Min – was also the author of Burma We Love (Calcutta, 1945).

- [1] See Kyaw Min, U (2013) A Glimpse into the Hidden Chapters of Arakan History, pp, 62-63. Yangon. See his leading role in the campaign for “Rakhine statehood or autonomy by any means necessary” Myanmar Politics (1958-62), V. 3, pp.223-224.

-

For substantive debates and discussions with respect to this above-ground political struggles see Kyaw Win, Mya Han and Thein Hlaing (1991) Myanmar Politics (1958-62). Volume 3. pp. 162-255. (Yangon: Central Universities Press). (Hereafter Myanmar Politics.)

- See Myanmar Politics (1958-62), V. 3., p. 192. Verbatim quote by Mr Abu Baushair, Member of the Parliament from Buthidaung Township

- Personal communications with the ex-Brigadier General Thura Thet Oo Maung, who was Head of Strategy based in Rakhine Command, Brunei, 2012. He was serving as Myanmar Ambassador to Brunei where I was teaching at the university.

- See Tat Ka Tho Sein Tin (2016) Myanmar’s Democratic Journey and Thura U Tin Oo (authorized biography) Volume One. Rangoon.

- Laura van Waas & Natalie Brinham, “The Statelessness Pandemic”, Project Syndicate, Oct. 15, 2021 at https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/statelessness-denaturalization-past-and-present-by-laura-van-waas-and-natalie-brinham-2021-10

- “Tatmadaw meets ANP ahead of hluttaw debate,” Frontier Myanmar, August 11, 2017 https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/tatmadaw-meets-anp-ahead-of-hluttaw-debate/

- “Tatmadaw meets ANP ahead of hluttaw debate,” Frontier Myanmar, August 11, 2017 https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/tatmadaw-meets-anp-ahead-of-hluttaw-debate/

- In one of his Burmese language addresses on the Rohingya identity, yhe late Brigadier General Aung Gyi, deputy-commander-in-chief in charge of the Army in Burma in 1961 noted the multiple identities of borderland ethnic communities of Burma, including Wa, Shan, Kachin, Chin, as well as Rohingyas.

- Aung San Suu Kyi Asks U.S. Not to Refer to ‘Rohingya’, New York Times, 6 May 2016 at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/07/world/asia/myanmar-rohingya-aung-san-suu-kyi.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Incitement_to_genocide accessed on 10 January 2022.

- Myanmar junta protests to UN migration agency about Rohingya Cultural Memory Center Junta’s foreign secretary says website contains ‘false and misleading statements and information.’ Radio Free Asia, 7 January 2022 at https://www.rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/protests-01072022173000.html

- For the first comprehensive academic study which treated Myanmar’s institutionalized destruction – not simply killings – of the entire Rohingya population using the genocide framework and the Genocide Convention see my 3-year-study jointly conducted with my wife and professional colleague Natalie Brinham (pen name Alice Cowley), Maung Zarni & Alice Cowley, The Slow-Burning Genocide of Myanmar’s Rohingya, 23 Pac. Rim L & Pol’y J. 683 (2014). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wilj/vol23/iss3/8